New Works: Mehlli Gobhai

An excerpt from the essay PICTORIALITY AND OBJECTHOOD by Ranjit Hoskote

“The most arid stretch is often richest,

the hand lifting towards a fig tree from hunger

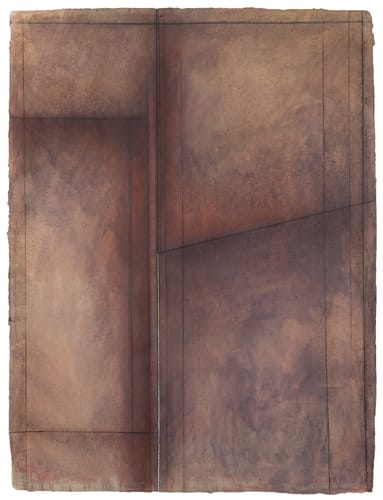

untitled, mixed mediums on constructed canvases, 60 x 60 inches, 2010

digging

and there is water, clear, supple, or there

deep in the sand where death sleeps, a murmurous bubbling proclaims the blackness that will ease and burn.”

– Frank O’Hara, ‘In Memory of My Feelings’

Surge and Absorption

Austerely refined as they are, in the taut linearity of their structure and the deep-welling penumbral richness of their colour, Mehlli Gobhai’s paintings have often been thought to be restful. Whether suggestive of cool metal, burnished leather, weathered stone or the edge of luminosity signing a margin of reassurance against the dark, these abstractions have been viewed as meditative pauses: they seem to offer their viewers a temporary reprieve from the frenzied music of life. Look more closely, though, and a different reality manifests itself. While many artists tend to organise their paintings as a pattern of intensity and slack, emptiness and fullness, producing a loose-woven rhythm, Gobhai develops his pictorial space as a field of competing intensities. He achieves this by diverse, ingenious means, including the ordering of masses through a grid of horizons or a forking venation of diagonals; the alternate layering and stripping away of pigment, which permits the surface to glow in its own light; the robust palpability produced when one thick sheet of handmade paper is stapled or glued on another, or one canvas is propped up against and attached to another; and the repeated scoring or pointing up of a line into a singular emphasis, like a chant or an augury.

Gobhai’s approach to his art is profoundly material, artisanal, workmanlike. His paintings, whether on paper or canvas, are built up like palimpsests, through the successive application, removal and addition of layers of acrylic, charcoal, graphite, zinc and aluminium powder, and pastel. Through these manoeuvres of staining, polishing, paring and burnishing, one layer becomes encrusted with another, sometimes; at other times, a substrate is lifted back into view from later accretions.

Gobhai retains the brush, that traditional symbol of painterly genius, only for the broadest washing-in of paint. He accomplishes his subtle effects of tonality by working his pigments and powders directly into the surface with his fingers, a set of rags, and wads of cotton. The gradations of grey, black, sienna, rust, olive and verdigris in his paintings change with the changing light and viewing position. Across these tones, Gobhai incises his ordering pattern of lines, sometimes marking them a stark white, as though chalking a marker of the intransigent human will against the organic inevitabilities of the earth.

Through the poetics that he has evolved over the last three decades, Gobhai refers strongly to the traditions of handmade votive and domestic objects, which were created lovingly and with meticulous attention in a lifeworld where their use was rooted in a continuity of impulses among mind, eye, hand and situation—rather than on the mutual alienation of these elements by technologies that instrumentalise the process of labour and render its products generic or immaterial.

A surge of primal energy crests in every one of Gobhai’s paintings: a continuous, percussive energy that collides with his picture surface; and which he shapes, with a geometer’s instinct for measure, into a system of modular forms. Gobhai crafts the ratios of his modularity through the classical device of the Golden Mean as well as, sometimes, the Fibonacci sequence. The forms into which he shapes the surge thus bear magnitude as well as direction: they are held within mutual relationships of attraction and repulsion; they resonate within a system of visual echoes and counterpoints, so involving the viewer in a deep absorption.

This is why, even as the surge remains in constant play in Gobhai’s pictorial space, the absorption ensures that the overall effect is paradoxically one of repose rather than of restlessness.