-

CAPUT MORTUUM

-

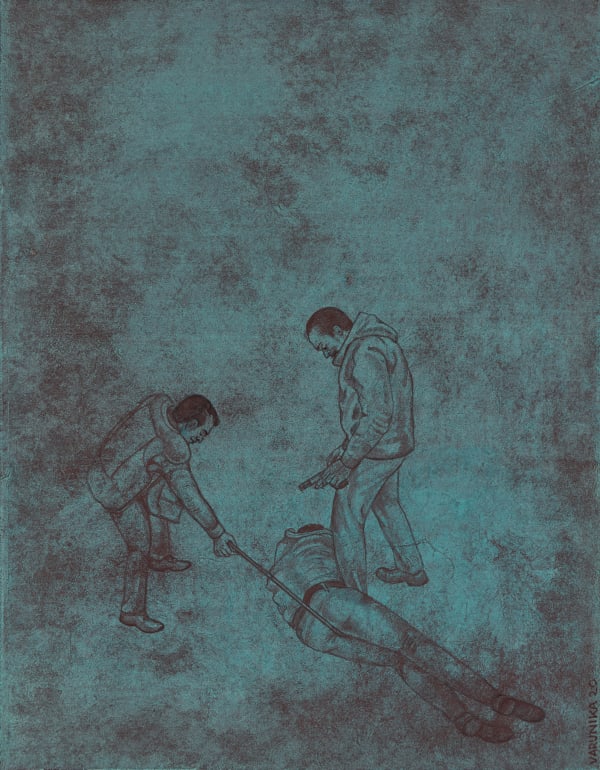

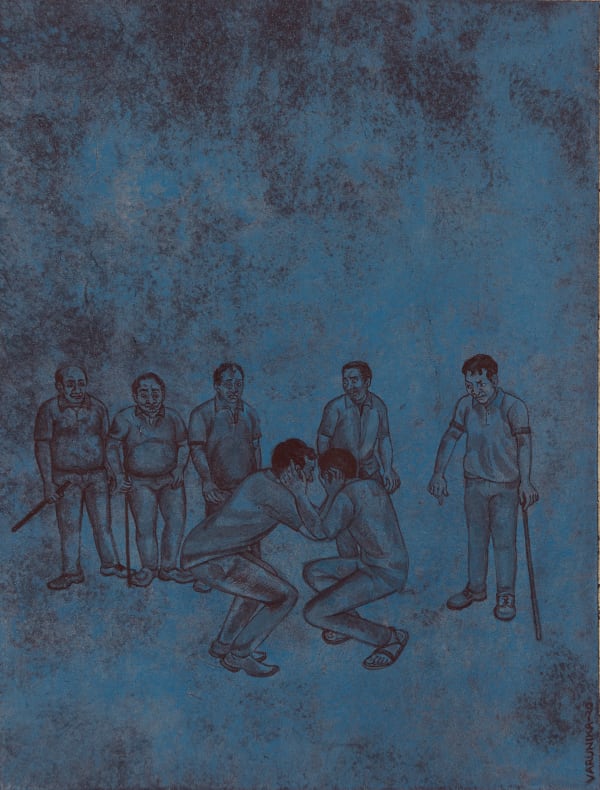

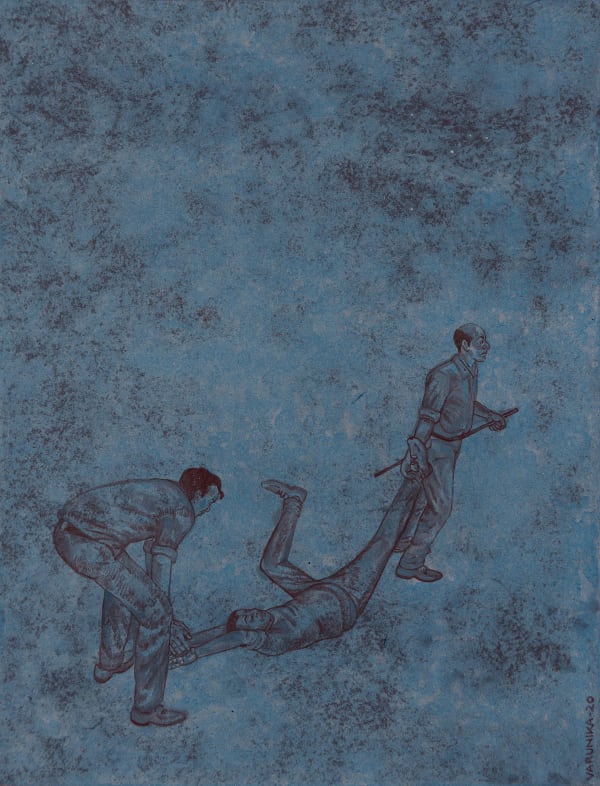

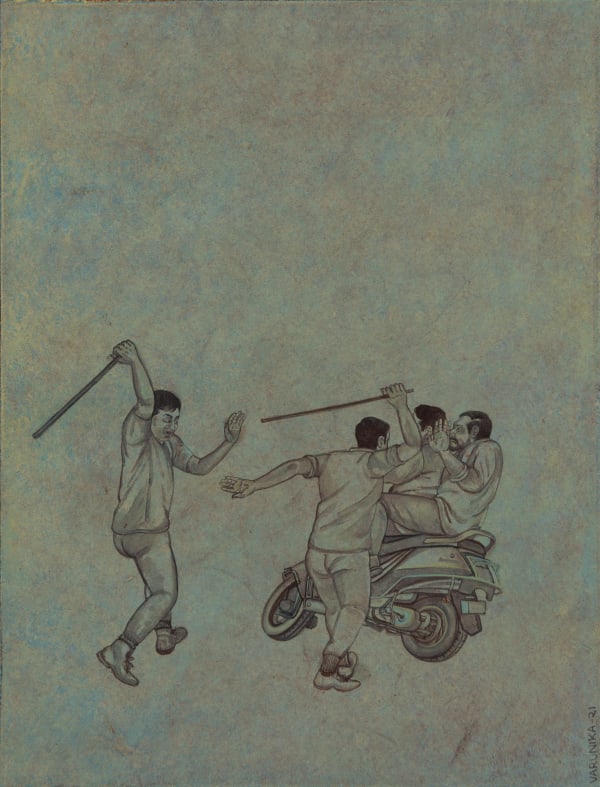

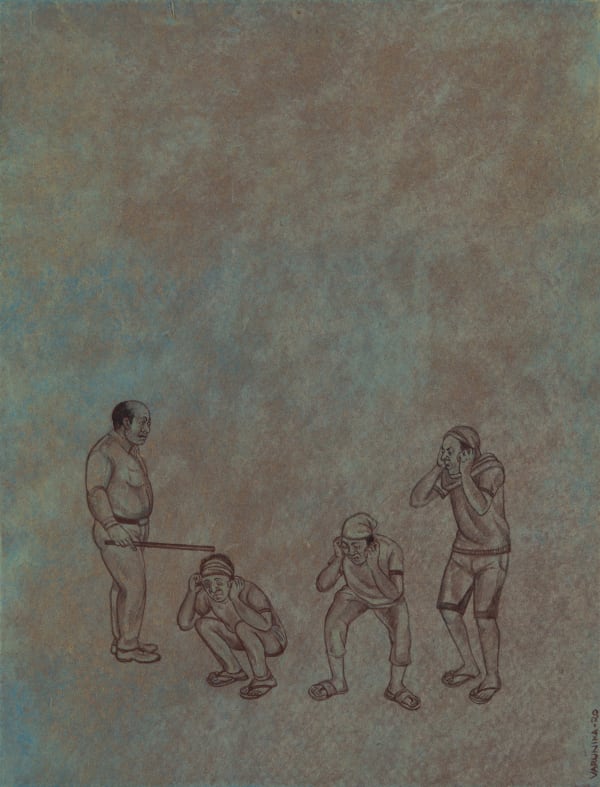

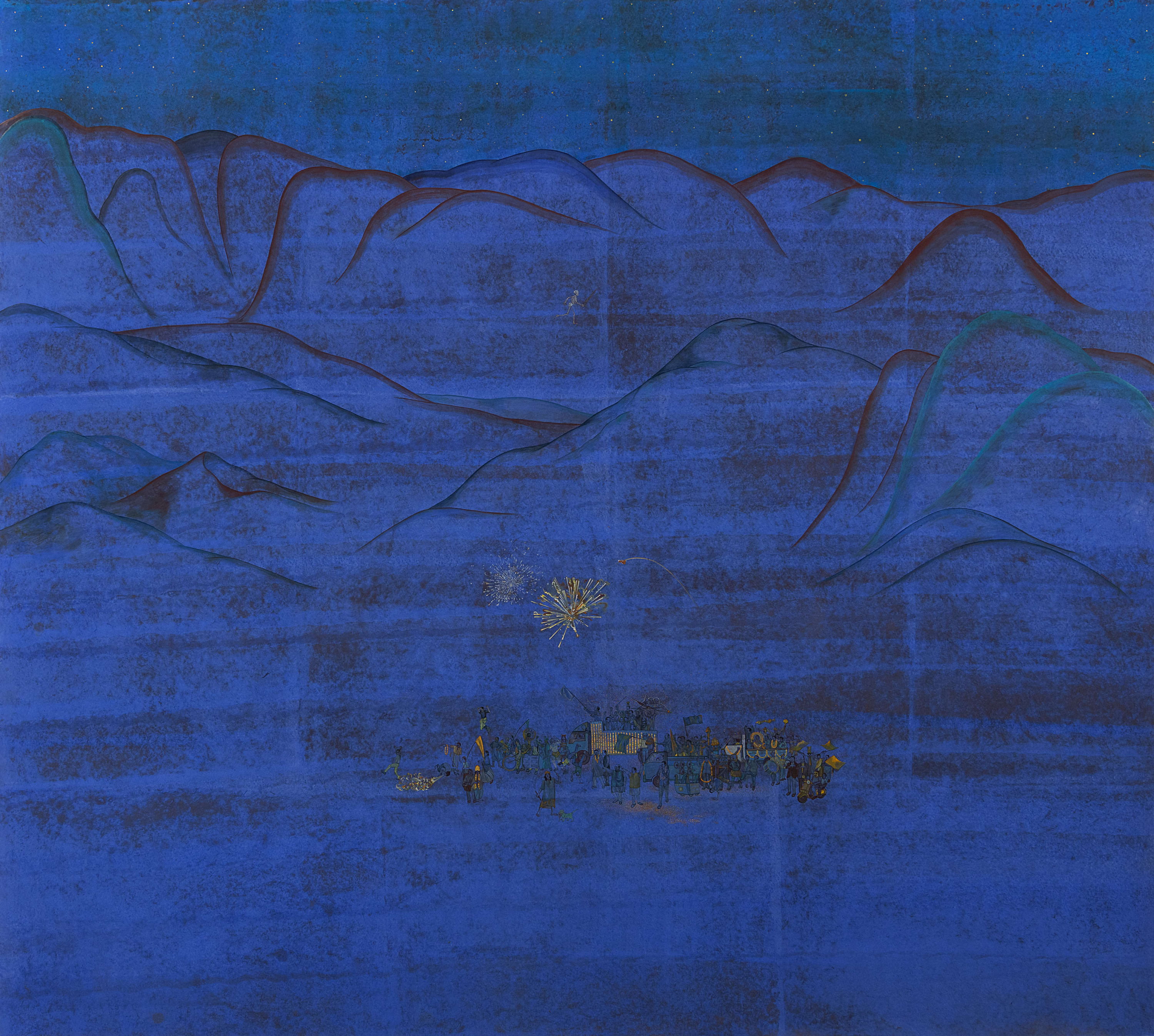

Caput Mortuum is a part of my ongoing work that highlights certain pivotal moments to reflect upon the violence consuming our world. It seeks to draw attention to the individual suffering that is increasingly becoming a part of the debris piling sky-high around us as we are thrust into the future. The series draws its title from the pigment Caput Mortuum (Dead Head), a synthetic Iron Oxide that resembles dried blood. It is symbolic of decay and decline. The choice of this pigment, unfamiliar to the Indian tradition, is at once a discreet denial of purist canons in painting as it is emblematic of our turbulent past. This pigment cast in thin washes onto the underlayer of each painting bleeds through subsequent layers of Cadmium Green onto the surface in the same way as historical injustices seep through the cracks of time to shape our present. It becomes a stain on a beautiful verdant land to remind us of the burdensome legacy of communal violence in South Asia.

-Varunika Saraf

-

MIASMA

-

-

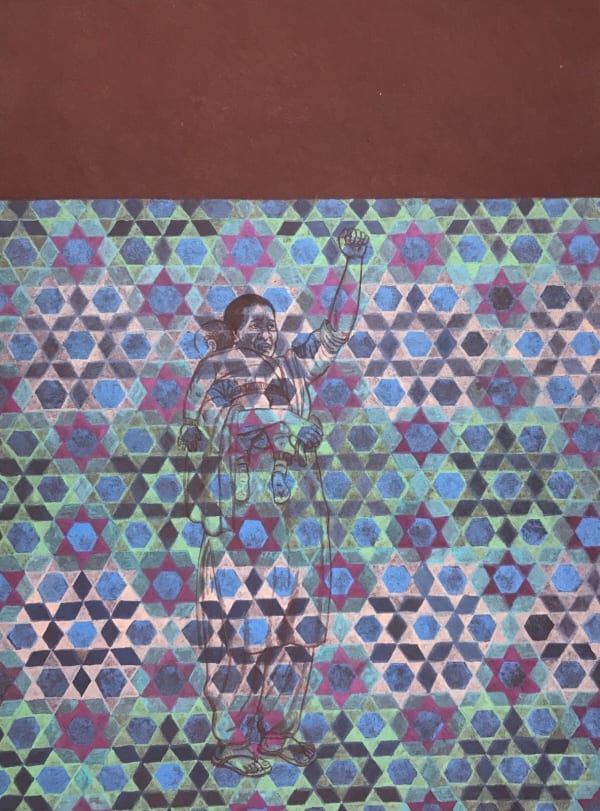

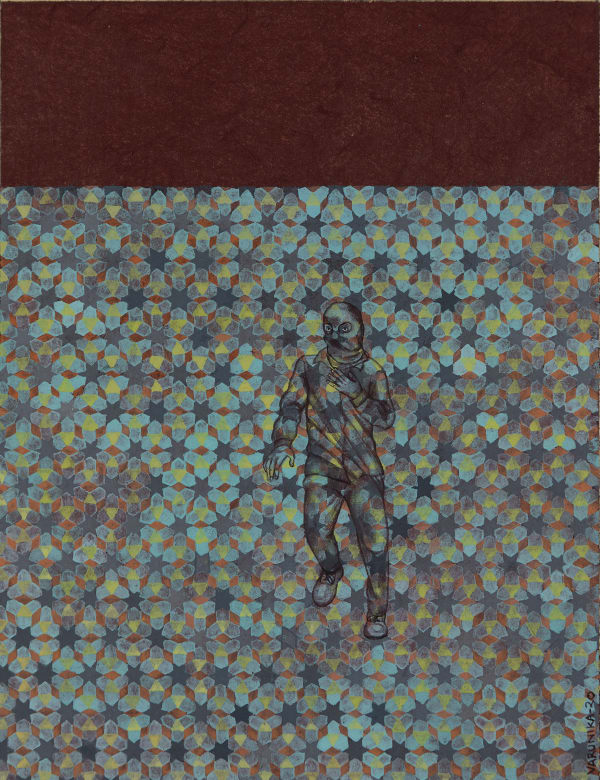

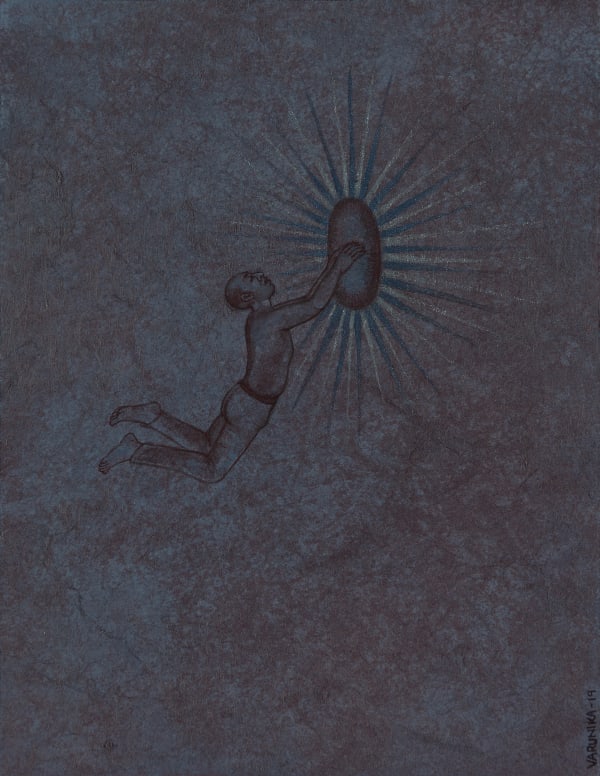

How do we stop the exponential rise of violence? Is it still possible to dream of an egalitarian society? Can we find love and hope amidst hate? Will we be able to heal the festering sores that riddle our world? How long will we continue to remain silent? To speak about a present besieged by brutal acts of violence, this body of work takes its name from the synthetic Iron Oxide pigment Caput Mortuum (Dead Head) that resembles dried blood. In alchemy, Caput Mortuum is classified as 'worthless remains'– the residue left on the bottom of the heating flask once the nobler elements sublimate. Perhaps, like our society, an outcome of a flawed experiment. Using this metaphor of decay and decline, I seek to highlight much of what we leave unspoken in our complicity and attempt to dispel the collective amnesia that sustains the cruel illusion called progress.

After grinding it into fine watercolour, I deposit Caput Mortuum in thin washes onto the burnished plane of the Wasli. It appears to haemorrhage through the overlying stratum of intense colours, staining the surface of the painting in the same way as historical injustices seep through the cracks of time to mould our present, just as wounds inflicted by hate scar our society. In this process, Caput Mortuum also becomes a marker of a past rife with injustice and comes to signify the complexity of our current predicament. The blots of bleeding colour disrupt the picture plane, positing the explicit imagery portrayed as fallouts of all that lies underneath, i.e., the effects of deep malaise and structural violence, and, at the same instance, become portents of futures that are yet to unfold.

The events inscribed onto the surface of each painting document the extraordinary struggles that people are facing and bear witness to life without power and political agency. I draw upon medieval imagery of interpretations and revelations to develop a language that allows us to process not just portents and spectacles but also anxiety caused by political and social upheavals. Drawing inspiration from Griselda Pollock’s seminal work that highlights the importance of remembering the past that “agitates the present” to warn us of the enduring threat of systemic dehumanisation, I engage with the ever-growing phenomenon of violence that is bringing us to the brink of annihilation. The language that builds on stains, scars and disruptions is further supplemented with ‘remediations’ of the iconography of miraculous and apocalyptic visions, specifically the Augsburg Wunderzeichenbuch, or the Book of Miraculous Signs and other depictions of infernal realms. My works are at once a reference to, a subversion and perhaps even a hijacking of complex and ever-changing processes that we call tradition. They are a result of deep love for and a grounding in the material processes, and at the same time, are shaped by a discomfort with the idea of tradition and what this word implies. Thinking through such imagery and recent events with equal dread and hope is a call for urgent action to unmake the future that current events have set into motion.

Varunika Saraf

2021

-

THOSE WHO DREAM

-

-

NOCTURNES

-

Who are we? What pasts shape our society?

‘We, The People’ is a series of forty-six works that attempts to chart an alternative timeline of the nation through the fissures and faults that structure our present. Drawing inspiration from Eduardo Galeano, who implores us to “search for the keys in the past history to explain our time”, this work maps our collective past and memory, highlighting lesser-known events that can shed light on our present. Moments from the history of modern India beginning with Margaret Bourke White’s heart-wrenching photographs of the partition and images of subsequent events such as the Union Carbide gas leak in Bhopal, the Narmada valley and the Chipko movement drawn from news archives are hand-embroidered onto individual khadi textiles inscribed with a map of the country. A map formed by an assemblage of tiny blots and bleeds created by tie and dye with carmine extracted from Cochineal (a scale insect, Dactylopius coccus), symbolising the blood that continues to be spilt in the making of the nation. -

PAINTINGS

-

Varunika Saraf

Vikas Band & Co., 2020Watercolour on Wasli backed with cotton textile

67 x 76 in

170 x 193 cm -

Varunika Saraf

“Love Is Contraband in Hell” (Assata Shakur), 2020“Love is contraband in Hell, cause love is an acid that eats away bars. But you, me, and tomorrow hold hands and make vows that struggle will multiply. The hacksaw has two blades. The shotgun has two barrels. We are pregnant with freedom. We are a conspiracy.” –Assata Shakur

-

Varunika Saraf

Let’s Tell It Like It Is, 2020Let’s tell it like it is’ is a call to go beyond the seductive and fallacious narratives that sustain the myth that everything is all right and recognise the problems consuming our world.

-

Varunika Saraf

Voices in the Night, 2020Watercolour on Wasli backed with cotton textile

67 x 76 in

170 x 193 cm -

JUGNI

-

MINIATURES

-

-

Saraf achieves a visual complexity through various techniques which include the use of the wasli board, watercolours prepared from natural and mineral pigments, dyeing, embroidery and block-printing, amongst others. Much earlier in her artistic career, Saraf had developed the technique of layering different kinds of paper on canvas, plain cotton cloth, and printed fabric to create a surface for painting. Her interest in natural pigments, both mineral and synthetic, which she mostly prepares on her own, allows her to expand the palette. Saraf’s painstakingly detailed images on rice paper, a surface she has been using since 2001, conceal a realm of conflict inside dense forests and architectural spaces and are imbued with the spirit of historical enquiry. These surfaces are richly illustrated with detailed patterns in which the narrative plays out, or rather unfolds. They compel us to look closely at the peaceful surface realities to experience the violence of our times. They are an elegy to that which mostly remains inaccessible or ignored.

-