-

Ali Kazim · Anju Dodiya · Atul Dodiya · KM Madhusudhanan · Mithu Sen ·

Mrinalini Mukherjee · Prabhakar Pachpute · Radhika Khimji · Simryn Gill

-

For the first time, four of India’s most prominent galleries – Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai; Experimenter, Kolkata; Jhaveri Contemporary, Mumbai; Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi – will come together during London Gallery Weekend for a collaborative exhibition, Conversations on Tomorrow, hosted by Sadie Coles HQ. As galleries increasingly move towards partnerships and international dialogue, the exhibition arose from early meetings of the International Galleries Alliance. Driven by a desire for meaningful and sustained collaboration, the galleries – each based in one of India’s major cities – will present a nuanced picture of art from South Asia and its diaspora. Co-curated, the exhibition brings together nine leading artists, including, Atul Dodiya, Mrinalini Mukherjee, Mithu Sen and Prabhakar Pachpute. Encompassing multiple mediums, the unique exhibition presents adiverse body of works that speak to the everdynamic concept of global South Asia and all its complexity.

-

“What comes after reason?” Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung asked last year.1 By addressing a strain of “reason” – a rational, canonizing, cerebral, and intoxicating form of thought prescribed by the West – Ndikung was adumbrating his intellectual resistance. In art, “reason” might suggest submission to the pervading institutional structures, and satisfying market predilections and aesthetic trends. For Ndikung, however, a departure and de-linking from “reason” would give way to the acknowledgement of what he calls the “multiplicity of beings, and the multiplicities of ways of being in the world – cognitively and phenomenologically”. It is in this spirit that this collaborative exhibition, Conversations on Tomorrow, presents the shape and variety of human terrains—both geographic and psychological—that manifest in and from South and Southeast Asia.

Across the exhibition, each artist cultivates an elastic approach that welcomes the complexity of human co-existence. Through diverse mediums, including painting, sculpture, etching and photography, the artworks speak to issues that, whilst responsive to each artist’s context, transcend them. Each piece extends itself to find universal resonance and offer a renewed understanding of our future. It is perhaps Ali Kazim’s watercolour, Untitled (Ratti Tibbi Series), 2017-18, that most directly addresses patterns of settlement and human interconnectivity. Shattered across a grid of nine white leaves of paper are fragments of terracotta vestiges from civilisations that once populated the Indus Valley around 3000 BCE to 1500 BCE. The variegated deposits form a collective portrait of extinct Harappan communities who revered and used its very matter to create functional items. The image, a visual trail into the past, simultaneously opens up the possibility of thinking forward to contemporary uses of land and shifts in settlement, and provokes the questions of what will be left littered across lands in the future.

Channel, 2014, a series of photographs by Simryn Gill, in its intimation of the conflict between human and ecological life, might suggest an answer. Day to day items –including fabric and plastic waste—cling to branches and wind themselves around roots exposed in a Malaysian mangrove, to the extent that they appear intrinsic to the landscape. There is a disquieting beauty in these objects that stray from the ocean to the land. But the images are singed with the pathos of human disregard for both possession and plant.

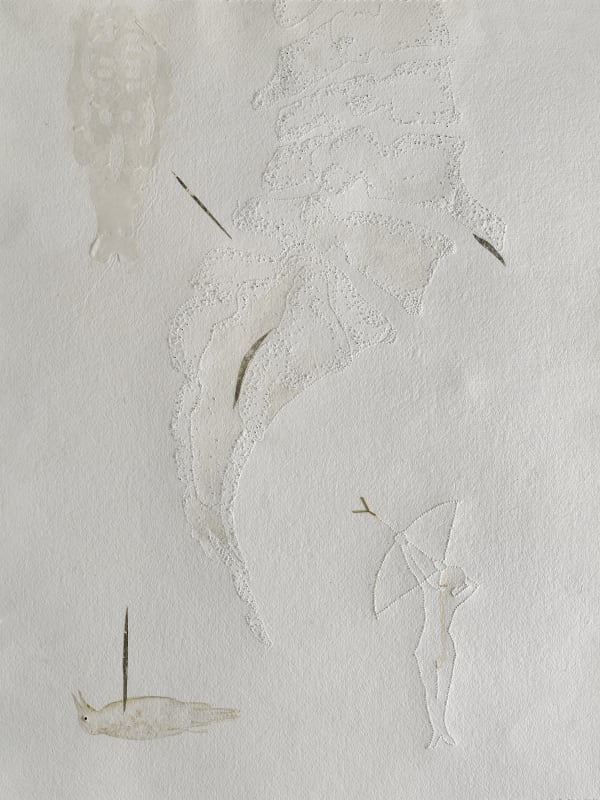

Mrinalini Mukherjee’s detailed and caring etchings of verdant landscapes contrastingly implicate the joy of being in nature. These lively images, like Landscape I, 1980, where trees loosen from their roots and dance, have a diaristic quality and form a tender record of Mukherjee’s observations and admiration for India’s ecology.

Prabhakar Pachpute expands on the volatile human relationship to land. His practice has long been invested in exploring humankind’s reliance on the earth’s abundance and the environmental transformations occasioned by this dependency. In Resilient Bodies in an era of Resistance, 2018, a network of soil-clump cutouts, arranged like a tunnel route to treasure, responds to the recent protests and collective action by Indian farmers against the threat of legislative disfiguration of agricultural rights. A body atop this mound strains from a weight mounted on its back, and Pachpute’s sculpture, Rattling Knot II, 2020, comprising a pyramidal mass doubling down on and almost consuming several pairs of legs, relates the exhausted worker’s body. In this apocalyptic world, the extractive practices and the political policies that skew them warp all.

These are challenges that are as local as they are international, as contemporary as they are historic. It might take the visionary thinking alluded to in KM Mudhusudhanan’s work, Conversations with Black, 2019-2022, to reach resolution. Across sixteen charcoal drawings, flattened to the extent that they appear as prints, he considers the malleability of belief systems—be they religious or political—specifically addressing the theory of classical singer Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan (1902-1968) who regarded art and music as forces capable of stimulating cross-cultural unification. In Mudhusudhanan’s incongruous patchwork of images, items appeal to this idea of music as a consolidatory force; a small gramophone is cradled in wire and a bundle of microphones form a bulbous mass. Miniature mannequins are depicted jostling with toy animals as monuments fall.

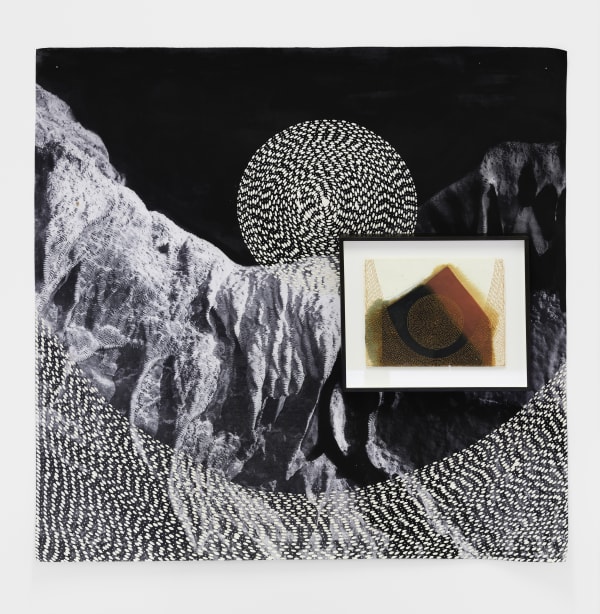

This “inventory of lost utopias”, as described by Nancy Adajania, shares in its discord with Atul Dodiya’s reloaded Wunderkammer.2 Encased in shallow wooden cabinets, with apertures shaped like easels, is a collection of trinkets integrated with a monochrome sequence of images. Each depiction is a citation drawn from Dodiya’s close watching and recollection of a seven-minute section of Hitchcock’s Blackmail that focuses on a fatal struggle between a woman and an artist. This storyboard, filtered through Dodiya’s memory and fragmented by his miscellanea, visible through the shape-shifting windows, invites more imaginative associations.

Where Radhika Khimji draws on an array of techniques, combining photography with painting and embroidery, it is to reimagine geographies. In dense and majestic images and installations, Khimji dramatizes and abstracts aspects of the environment. Photographs that once captured caves in the Al-Hajar mountain range in Oman are turned into surfaces for embellishment. Small lozenge markings, based on beads from the god Krishna’s necklaces, appear like ideograms. The tightly wound patterns churn and revolve, open and seeking interpretation.

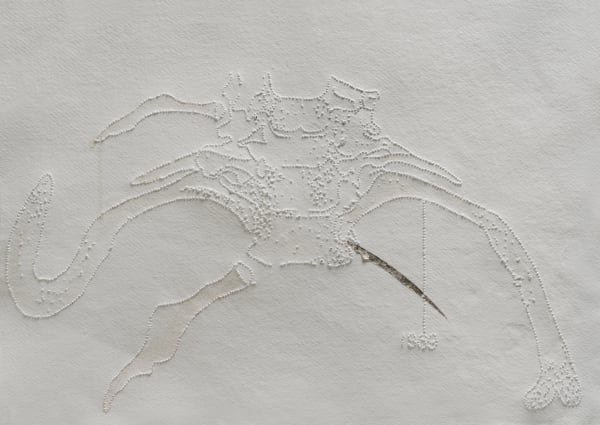

The simplicity of Mithu Sen’s mark making belies the intensity of her work, Until you 206, 2021-2022. With a pinpoint she pierces paper to form a suite of images that itemise the human skeleton. In Sen’s idiosyncratic anatomical diagrams bones are shown shattered, hands are bloodied and each body part is labelled with a date. The dates reference a timeline, accessible via QR code, which records outbursts of violence in India’s post-Independence history. It is not that Sen consigns these incidents to the past; she deploys them as part of an incomplete monument that anticipates the persistence of brutality. Bound up in each image is therefore pain and premonition suffused with acute anxiety.

Anju Dodiya’s figurative four-piece tableau explores emotional intensities that fester and flare up in the home. A hand here bleeds too, speared by the stem of a plant. Dodiya’s canvases are plumped up by padding and struck through into grids. Across them women are disfigured, seemingly by their pursuits and the domestic settings where many were confined during the pandemic. With flashes of colour there is, however, allusion to the small pleasures—books, gardens, food— that some were able to ace. As a dichotomous view of this period, the images sit between joy and pain, celebration and commemoration.

Conversations on Tomorrow is, in its broadest sense, a provocation to, as Ndikuj suggests, advance perspectives and diffract understandings of place and people. Throughout the works, the interplay between bodies—visible or assumed— and those very real and those imagined environments attests to the versatility of the multiple global South Asias that abound today.

Dr Cleo Roberts-Komireddi

1 Ndikung, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng, ‘What Comes After Reason?’, Spike Art Magazine No. 66, Winter 2020

2 Nancy Adajania, ‘The Registry of Things Past: ‘Neither you are aware, nor the police’, catalogue essay for the exhibition ‘Babel’ held at The Guild Alibaug, 2017

-

Mithu Sen

-

'Until you unhome' will be a set of uncolored, uncontroversial, and virtuous happy-prick-drawings, and (un)home is an

(un)judgemental space which serves as a disclaimer and an exercise in perceiving what the images are and are not. We seem to

enter into the gridlock of a conceptual binary that seeks to negotiate the effects that images generate, as well as the

conundrum of seeking happiness through art and the larger historical purpose.

This (un)home is a (un)judgemental but undeniable, un-ignored space that experiences the immateriality, the devoid.

confirming the validity of our existence and our experiences. All existing things exist by comparison to nothing. This devoid is

self-defined and it defines everything else.

- Mithu Sen

-

Mithu Sen

UntilYou 206

1947 – present

56 uncoloured happy prick drawings, Zarina, metallic paper, watercolor ink, violence, riots, mass graveyards, lynching tools on handmade paper, QR code

457.2 x 213.3 cm / 180 x 84 in -

Atul Dodiya

-

Seven Minutes of Blackmail, an exhibition held in 2019, Atul Dodiya explored his deep interest in the medium of film, where his signature painting style is often mistaken for photography. Through this body of work Dodiya pays homage to the genius of Hitchcock's Blackmail (1929), where the film encapsulates an eerie depiction of effective emotion, impulsive reactions and a chase. Through his own reading of the film, the artist has crafted a language that is both similar and dissimilar to its source. Dodiya has often used the cabinet of curiosities, a Wunderkammer reloaded for contemporary times, to perform an annotative function, writing footnotes as it were to the unfolding narrative. These particular cabinets shift focus from their shuttered black- and-white palette- windows, which act as a poetic caesura to a lively bric-a-brac of art history and popular culture. Here figurines and curios found in the flea market rub noses with museum magnets bearing the seriousness of high art. If this resembles a pleasing disorder of things, what we have before us is a carefully arranged score of harmonies and discordances.

-

Atul Dodiya

Untitled

2018

Three wooden cabinet installation with painted glass, framed photographs and found objects

237.7 x 405.4 cm / 93 9/16 x 159 5/8 in -

-

Radhika Khimji

Brittle like Biscuit

2022

Oil on Dye-sub print on polyester & birchwood ply 249 x 167 cm / 98 x 65.7 in

120 cm / 47.2 in diameter -

Radhika Khimji

Feathery House

2022

Oil and Dye-sub print on polyester & oil and thread on photo-transfer on paper 99 x 99 cm / 38.9 x 38.9 in

20.6 x 26 cm / 8.1 x 10.2 in

-

-

Simryn Gill

Channel

2014

All works:

Gelatin silver print / Ilfochrome print Edition 1 of 2 + 1 AP

31.6 x 32 cm / 12.4 x 12.5 in, each -

-

L: Ali Kazim

Untitled

2022

watercolour pigments on paper 56 x 76 cm / 22 x 29.9 inAJ_KA_A_095

R: Ali Kazim

Untitled

2022

watercolour pigments on paper 56 x 76 cm / 22 x 29.9 inAJ_KA_A_096

-

Ali Kazim

Untitled (Ratti Tibbi Series)

2017-18

Watercolour pigments on paper 56 x 76 cm, eachAJ_KA_A_058

-

Ali Kazim

Untitled

2022

Terracotta Dimensions variableAJ_KA_A_098

-

-

Mrinalini Mukherjee

Etching

-

Anju Dodiya

Watercolour and charcoal on fabric combine stretched on padded board

-

K.M. Madhusudhanan

Conversations with Black

2019–2022

Charcoal on paper

73.6 x 53.3 cm / 29 x 21 in (Set of 16) -

Learn more

Conversations on Tomorrow: Sadie Coles HQ

Archive viewing_room